Film, Photo Series, Printed Matter

2007

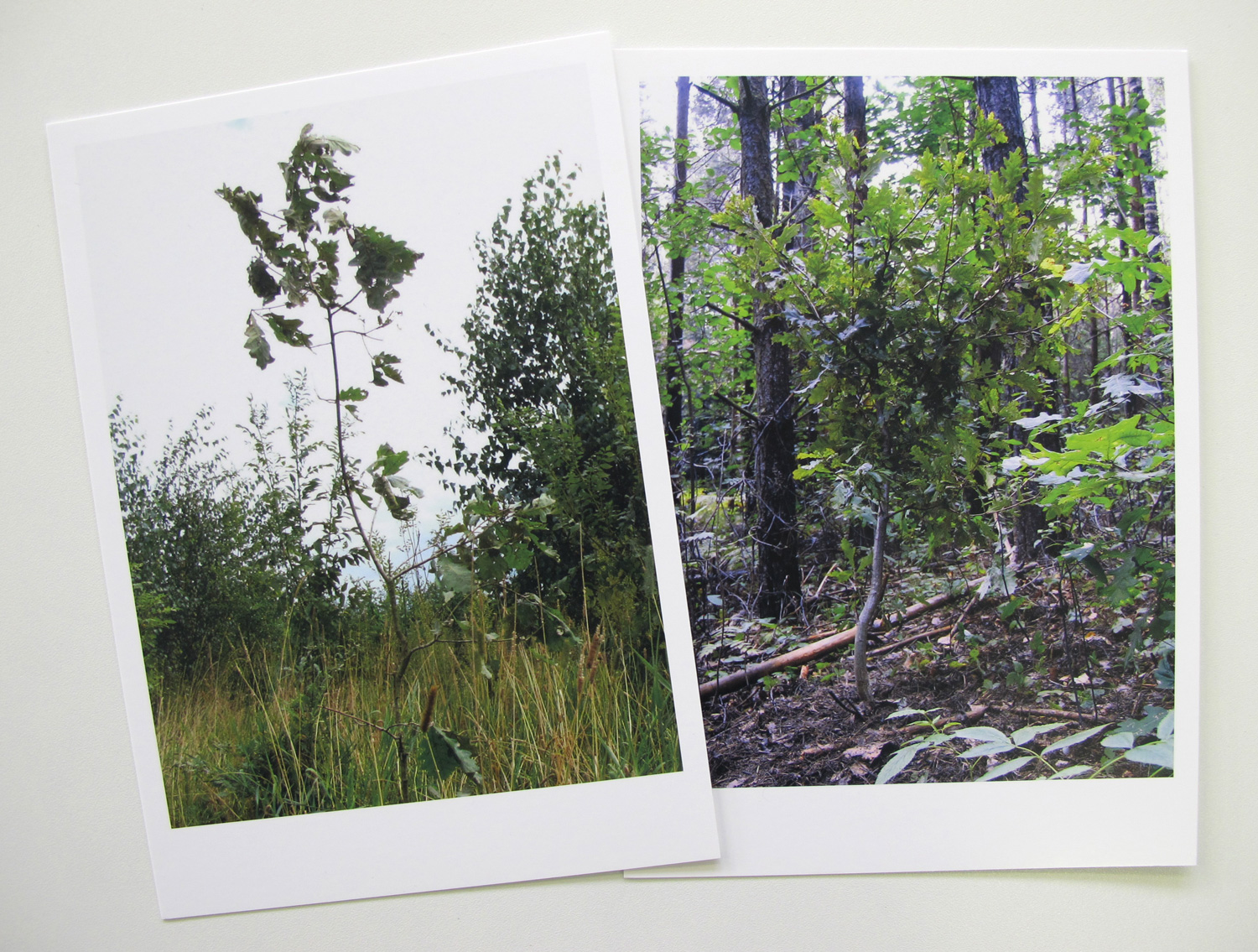

All Alone among the Stars involved the exchange of two young oak trees of similar size and age between 13HA forest and Bialowieza National Park. Digging out a tree from the primeval forest and planting it amongst the young trees in the Netherlands provoked questions about the incommensurability of artificially constructed, temporary woodland and real nature, while transplanting a young compensation tree to Bialowieza also planted a seed of doubt about the legendary untainted nature of the ancient forest.

The ancient Bialowieza forest is one of the last remaining virgin forests, which once covered the lowlands of Europe. The unfathomable might of its natural ecosystem has inspired scientists, environmentalists, historians, and artists since the eighteenth century. Locals, as well as tourists, are drawn to the overwhelming magical experience they find in the primeval chaos of trees towering tall, having fallen over, shooting up, and decomposing. As Simon Schama writes, there is something at the heart of the forest that remains irreducibly alien, impenetrable, resistant’ – ‘its irregularity dreadful, sublime, perfectly imperfect.’

The 13HA forest near Heeswijk in the Netherlands is the opposite of awe-inspiring primeval wilderness. The trees in this modestly sized wood were all planted mechanically in one go, at an appropriate distance from each other, now reaching the same unimpressive three-year height. This wood is not only situated in the culture of the Netherlands, where nature has been tamed and landscape has been cultivated for centuries but as a CO2 compensation project, this wood can also be seen as the ultimate outcome of modern man’s distorted relationship to the natural environment: a tiny symbolic gesture of retribution for ongoing global exploitation and destruction. Half of the 35,000 trees in this project have already been designated for harvesting in 2025 when they will be less than twenty years old.

All Alone Among the Stars

#1 Permanent intervention at 13HA and in Bialowieza Forest

#2 Two framed photos (30×70 cm.) & 2 postcards (A5) distributed for free

#3 HD video of the young ‘Dutch’ oak tree in Bialowieza Forest

Commissioned by: 13HA, Heeswijk-Dinther, NL

Thanks to: Krzysztof Wegiel, Bas Helbers

Background information of 13HA:

2001 The farm stops functioning like a pig farm

2002 The Start of HOP design. HOP design works with Afzelia (tropical wood) to prepare his furniture. The origin of this wood in unknown. It is imported through Germany and doesn’t have a FSC registration number

2003 The first art event takes place.

2005 There are 35.000 young trees mechanically planted on the field. Corporation Bosgroep Zuid, Het Groenfonds, and the government have made this possible. These organizations are still involved in CO2 Compensation regulations

2025 The amount of the 35.000 young trees will be cut in half. The cut-up wood will be used for the timber industry and will be used as wood burned for private heating.