Conversation

Marjolijn Dijkman and Kris Dittel

Kris Dittel Many of your works seem to deal with the larger questions of humankind and the human desire to know, to discover and to solve the great unknowns. Would this description fit the way you approach your topics?

Marjolijn Dijkman Yes, I think so. That’s also what for instance History Rising, a book I worked on with Jes Fernie, was about, with its enormous topic of the representation of history. Or the project Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, a large image archive consisting of photographs made during ten years, showing how people adapt to and alter their surroundings around the world. I’m interested in the relations and often contradictions between the individual and the universal. My working process involves extensive research and collaborations that investigate collective narratives in relation to the public domain and the commons.

KD The image essay Radiant Matter, which also lent its title to this book, is a captivating sequence of historical images that are concerned with the human body and to the cosmos. Earlier you told me about one of the motives, the Zodiac Man, a medieval representation of the human body and its alignment to the moon, the stars and their constellations. This body-cosmos connection is commonly depicted throughout history – also bringing to mind pagan myths and ancient medicine, where the effects of stars and stages of the moon had an effect on health and healing. If we think of it from the perspective of modern science, it’s interesting how humanity ‘tamed’ some of these powers coming from the universe – rays and radiations – and further reproduced and used them, for instance in medical science and technology.

MD This is what I found fascinating as well. For example there are gamma rays, the most violent cosmic waves in the universe, which we use on our own body to heal cancer, an illness that could be caused by radiation of an atomic bomb – a weapon, which is also replicating these gamma waves. I find this incredible, how cosmic forces relate to science, cosmology and the body … there’s something almost mythical about it. It brings to life a cosmological worldview, which perhaps got lost in all these technologies – in the clean hospital rooms and in the military strategies. But there still is a relation between all these things if you like.

KD Today when branches of scientific disciplines are built on exact sciences (computation, mathematics, physics), it seems there is a very conscious shift away from any spiritual or mystical modes of thinking and influences. Is there still space for metaphysics or is our way of understanding predominated by more ‘factual’ knowledge?

MD I guess they always go hand in hand. When new scientific discoveries or technologies are developed, pseudoscientific and spiritual movements adopt these very quickly in the most creative ways. I would say people have always believed that they are part of something larger, and try to find ‘proof’ in science for their own purposes. I think for scientists it can be very difficult to relate to spiritualism or science fiction, because people apply what they do in a completely different way, with for instance even religious belief systems attached to them.

KD Recently I read an article about the discovery of seven new planets around a dwarf star called TRAPPIST-1. The article included a short video where a NASA spokesperson was talking about the fact that finding ‘another earth is not just a question of time, but it’s a very fundamental inquiry for humanity : are we alone?’ This question truly reminded me of a sci-fi scenario and I found myself somewhat surprised that it was vocalised in this context so directly.

MD Yes, I think our current period is very interesting because it seems that this quest is really back on the agenda and in the public imagination, which is quite an interesting phenomenon. From the United Arab Emirates Space Agency founded in 2014 to China – where they opened the world’s largest single-dish radio telescope (FAST) in September 2016 that is also intended for SETI research (search for extraterrestrial intelligence) – space travel and the search for extraterrestrial life are fields reviving worldwide, and are expanding to involve private companies as well as governments.

KD It seems that scenarios we would hear about only in science fiction are entering the reality of everyday life: people are being recruited for a Mars mission, self-driving cars are being tested, artificial intelligence and machine-learning is happening right in front of our eyes. Do you think science fiction plays a role in what way these questions enter the public imagination? Does it predispose us perhaps to the acceptance of technical developments, and also shape the ethical and moral discussions around these subjects?

MD I guess in this field there’s a spectrum ranging from gloomy unsustainable-future perspectives to strangely optimistic scenarios for humanities’ colonisation of space. Some say we need to advance our bodies and move into space because of the catastrophes that we face here on earth. These kinds of ideas reflect the extremes of our current situation, with techno-optimists on the one side, who believe technology will solve our problems, and doom-scenario thinkers on the other side, who believe it’s already too late to save our planet. In the more speculative fields of science, fiction is definitely present. In SETI research, as an example, they are looking for other civilisations according to something called the Kardashev Scale. This scale is part of a thought experiment by the Russian astrophysicist Nikolai Kardashev, who imagined alien civilisations according to a scale from one to five based on their technological advancements and the amount of energy they are able to harvest and use. Our civilisation here on earth today is a Type 0 on this scale. Some think that in about 100 to 200 years, we will be able to become a Type I civilisation and be able to sustain ourselves here on earth solely from the energy of the sun. Type II can harvest all the energy of the sun in its solar system, and Type III can control the energy of its entire host galaxy. I think this kind of astronomical research is very much connected with science fiction – the kinds of alternative civilisations we imagine reflect of course our own worldview, and the period of time we live in. Such research involves a projection into the future of civilisation from a subjective worldview and may reflect more of our own ideas about the progress of our civilisation than other alien forms. The starting points of this kind of research are not neutral or objective, they are related to a culture and its ideologies.

KD Speaking of science fiction, you earlier mentioned Stanley Kubrick’s iconic movie 2001: A Space Odyssey in relation to your piece That What Makes Us Human . The opening scene of his film depicts the moment when human cognition started to evolve, when a prehistoric human uses a tool, a bone, for killing another. At the end of this brutal scene the prehistoric human throws the bone into the air, the scene is cut and in the place of the bone we see a spaceship and the story continues in a sci-fi setting in the far future. Your work consists of a silicon replica of a human hand and a titanium 3D-printed replica of a meteorite, and its title, That What Makes Us Human, directly refers to the universal questions we spoke about earlier.

MD Space exploration is often seen as one of the most advanced things that we can do as humankind. The rhetoric of the optimistic space discourse suggests that the moment we leave our solar system and live elsewhere in space, we will be free – liberated from the cradle of earth and so technologically advanced that we will no longer depend on our ecosystem. This work of mine you mention is analogous with Kubrick’s famous scene. The prehistoric bone as a tool or weapon transforming into a spaceship presents progress in an ambivalent light. The title was part of the entire research project included here. A lot of the works within this publication reference artificial intelligence, post-human theory and extraterrestrial life to explore the question of what makes us human, what is human? When I purchased a meteorite in the shape of a flint stone, fitting so well in a human hand, almost like it was purpose made, all these ideas around human evolution and progress came together. This metal ‘flint stone’ arrived on our planet fifty thousand year ago, which was also the moment in time when, according to the theories, humans ‘became human’. This meteorite came to the earth as part of a larger meteor Canyon Diablo’, apparently with an impact of around 10 TNT – about the same as the first hydrogen bomb ever tested. When scientists, after decades of debate, proved in 1960 that the crater where this meteorite is from was created by a meteorite impact, it was proven by the fact that the impact created the same kind of high-temperature melting process in the earth as an atom bomb creating the silica minerals coesite and stishovite. These things combined – a meteorite in the form of a prehistoric flint stone, arriving to earth with the same impact as the first hydrogen bomb – create some kind of poetry that implodes the chronological narratives of human history and technological progress.

KD As part of your exhibition at Onomatopee in 2016/17 we showed this work together with the film Prospect of Interception, produced for the 11th Shanghai Biennale. The film is an animation of a meteorite rotating in space. The narration of the film is composed of quotations from various sources in several languages. I was wondering if you had any kind of criteria or method when selecting these quotes – were there for instance any keywords, moods or interests that you were aiming to highlight?

MD It worked similarly to the way I assembled the images for Radiant Matter from many different sources and fields. The sources of the writings are ranging from popular science, astronomy, cosmology and space exploration, to more spiritual, religious approaches to life in outer space, the cosmos and our place in the universe. There’s also a part of the texts coming from cognitive sciences – thinking about intelligence and consciousness, and ranging from spiritual to more scientific approaches. I was looking for a variety of voices, from utopian and pessimistic visions to more factual and objective descriptions. The text approaches the simulated asteroid in the film sometimes as a threat, and other times as an opportunity or possibility for a utopian society in space. The two-hour text orbits around this fictional celestial object from this variety of perspectives, constantly trying to find equilibrium between those two extreme positions. I am interested in when different texts come together to make new connotations that arise with this proximity. As an example, the factual descriptions of an asteroid as a celestial body can take on new social, political or even spiritual meanings when it is surrounded by other texts about a body in a system.

KD Your work Mirror Worlds is inspired by the heliograph. I came across the double meaning of this apparatus which functions as a telescope for photographing the sun, as well as a signalling device to call for help or reveal your coordinates. There is a twofold movement at play: it uses the light of the sun to communicate but also to observe the sun itself. Again, this work brings together various stories, some with a more spiritual narrative, others with a rather scientific approach.

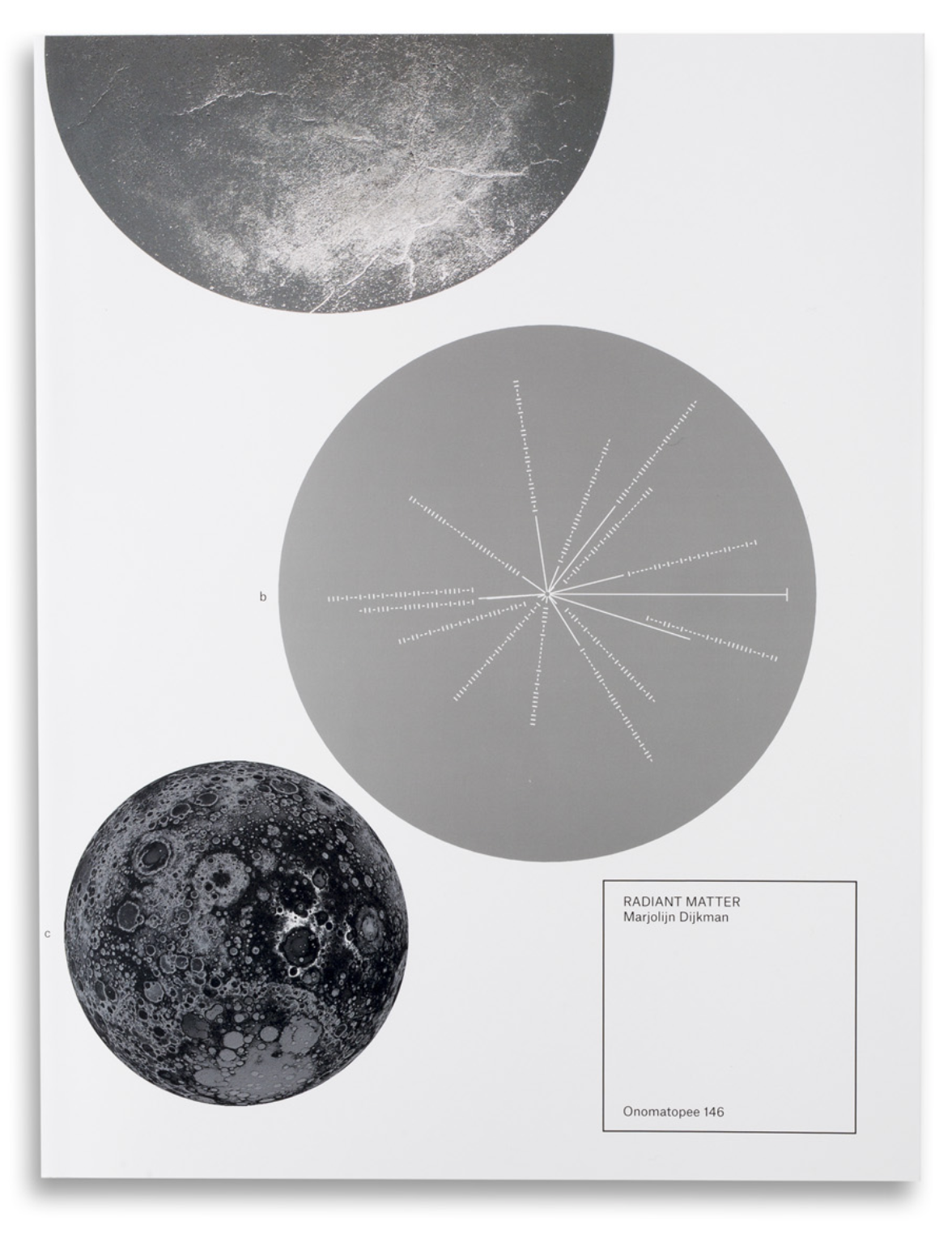

MD The inventor of the predecessor of the heliograph, the heliotrope, Carl Friedrich Gauss, developed it as a long distance communication tool and used it for one of the first recorded attempts to communicate with extraterrestrial life. It was a very futile attempt due to the limited distance he could reach, but his idea to say ‘Hello, we’re here!’ is a very essential human impulse. Currently, there is much discussion and debate around messaging extraterrestrial intelligence (METI). If we communicate with a more advanced civilisation, will they be friendly with us? Will they help us with technologies that can help us to solve our problems or will they destroy us? Again, here are the positive and negative aspects of communication, which I really found interesting. On the one hand a heliograph is used for military application and communicating strategies, and on the other hand when a ship gets wrecked sailors use it to call for help. Mirror Worlds is also a magic mirror, with an image hidden inside of it. The image reveals itself by sunlight or when an artificial light source is pointed at it. There has always been a relation between imaging, communication and censorship – revealing or not revealing. For instance, magic mirrors have been used for different kinds of sun-worshipping rituals, but also during a period of oppression – from the 16th century up to around the 18th century – in Japan when Christianity was forbidden, these hidden images of Christian crosses created secret altars. The magic mirror part of this installation is made by Akihisa Yamamoto, a magic mirror maker based in Kyoto who learned this almost lost, ancient craft from his grand-father. The drawing inside the mirror was produced together with Dutch radio-astronomer Roy Smits working at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON). Together we made an updated image of the solar pulsar map that was sent out of the solar system on the Voyager Golden Record, which was compiled and attached to the Voyager 1 in 1977 by Carl Sagan. The content of the record is a compilation of 116 images, sounds and songs from the earth, made to last one billion years. The Voyager 1 is currently the furthest man-made object in space and on the cover of this record is a map with the coordinates of earth to locate us in case possible intelligent alien life forms intercept the spacecraft. The Golden Record map reveals earth’s coordinates in our galaxy based on pulsar patterns, which are made by neutron stars that rotate in different rhythms. There are binary codes on the plate to identify these different stars. It is now very far into space but I learned that that map is unfortunately outdated according to the latest pulsar data. Even if another form of intelligence could intercept and decipher this map, the information appears to be incorrect, so they would not be able to find us.

KD It sounds as if we are still not completely sure if we know our own coordinates!

MD Yes, just like travelling through space is an unknown territory. I read that some space programs are imagining to use pulsar-based navigation systems to travel far distances in the future, also to use these systems to find their way back when we leave our solar system. So the map is not only developed for possible extraterrestrial intelligent civilisations, but also for ourselves, to know our place in the Milky Way galaxy. When you think of the impact for instance of The Blue Marble photograph – an image of earth made from the moon in 1972 – which is by now considered to be one of the most distributed images in the world. It was a great stimulus for environmental awareness and the idea of globalisation. Having a better understanding of our place in the cosmos could really help to relate differently to our planet.

KD Your work Shifting Axis refers to the moment in 1851 when a discovery changes and challenges our view as humans towards a larger system, affecting science, religion and our imagination. The work is based on Foucault’s pendulum, which demonstrated for the first time how the earth rotates around its axis by marking a shifting elliptical shape. You manipulated this pendulum, which creates a much less harmonious shape instead, so that it draws deformed patterns into fine sand. I would be curious to hear more about what your motivation was to manipulate this device?

MD As a scientific tool, the pendulum proves that the earth is spinning and that this is a steady process – if it would not be stable, we would have a problem on a catastrophic scale. The pendulum of Foucault was made at this very important moment in time when large scientific demonstrations showed people these newly discovered physical phenomena. My fascination for the pendulum is indeed that it reflects at the earth from a larger perspective, just as The Blue Marble did almost two centuries later. Science fiction often imagines our world within another large-scale scenario – in an ice age or a global disaster for instance. This is a thought experiment and Shifting Axis is also a form of science fiction like experiment, where the world appears to be in chaos according to the movement of the pendulum, which is creating these constantly changing mesmerising patterns of orbits in the sand. While witnessing this fictitious world in chaos, you become almost hypnotised by the pendulum’s movement. The work reflects on the contradiction I feel – the world is in this chaotic state and at the same time I am not really able to respond or to do something on it’s needed global scale; and often I feel quite disempowered by the scale of things.

KD I noticed that this work, like many others, is returning to important scientific moments in European history of the last centuries, the 18th and 19th century in particular. What fascinates you about this period of time?

MD Yes, it’s an interesting period of time, which I’m often drawn back to in my research, a period that is connected to many of the foundations of knowledge that we take for granted now. My practice has been influenced by the project LUNÄ I initiated in 2011, which also reflects on the 18 th century through The Lunar Society in England and its influence on developments in science, politics, industry and society. This informal society consisted of an influential group of industrialists, poets, inventors, doctors, and ‘natural philosophers’ who met monthly between 1765 and 1813. Members included James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, Joseph Priestley and Erasmus Darwin. The society convened at the full moon and participants discussed their latest research with the aim of exchanging thoughts and experiments, and at times developing projects collaboratively. Three centuries later, I revisit this moment of historical significance with the participatory work LUNÄ. I produced a facsimile of the original table where the Lunar Men met to provide a context to speculate and broaden the possible topics the original society might have discussed, and explore new ideas within these fields. Since January 2011 I have used the table in different locations, always around the full moon, for an ongoing series of critical discussions, expanding from the new scientific and industrial developments that occupied the Lunar Men to include art, education and social rights. These LUNÄ talks have been part of the research for several projects and are a way to actively engage audiences in my research process where I exchange with scientists and thinkers from different fields of expertise.

KD In 2016 you organised a series of LUNÄ talks around the topics of deep space, deep time and deep evolution. Two of the talks took place in Drenthe, a province in the north-east of the Netherlands, which is a notable area, not only because it has been populated since prehistoric times, but also because it is a very significant place for astronomical research, hosting ASTRON. At this location, with its deep history and status as a centre of astronomical research, you brought astronomers, geographers, anthropologists and artists together with the interested public. Do you think of these LUNÄ events as similar public ‘demonstrations’ – a moment when scientists can share their knowledge and fascinations with each other, and bring it to the public sphere?

MD Yes, I find it really interesting to explore the boundaries of art, society and science, and think that art can bring a different relation to the world just as scientists can. As artists we are free to make more subjective interpretations and speculations, which a scientist is not supposed to be able to do within their research. Together we can connect the discourses and see if something valuable could come out for both. One of the important aspects about the conversations of the Lunar Society, is that no minutes or notes have been made of the original discussions, leaving room for interpretation. It calls to mind the time when art, ‘natural philosophy’ and society were not yet divided up into their separated discourses and specialisations.

KD One of the LUNÄ talks concerned deep space, a branch of astronomy and space technology that is directed at the explorations of distant regions of outer space. Although there are various scientific tools and devices, like the Hubble telescope, to map these distant destinations, when one reads about such topics, such as in NASA’s announcements it sounds as if the mapping involves a large portion of speculation.

MD It was the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens, who wrote Cosmotheoros: or, conjectures concerning the inhabitants of the planets [in 1695], which is considered now to be the first piece of science-fiction writing that speculates about life outside Planet Earth. Speculation and fiction have an important role when it comes to scientific discoveries, but sometimes these ideas were somewhat far fetched. The astronomer William Herschel, a member of the Lunar Society, thought that the craters of the moon were lunarian cities and dwellings, and that the sun was inhabited by alien civilisations. Herschel’s thoughts about extraterrestrial life seem a little naive to us now. Yet Herschel discovered Uranus, was right about exoplanets and galaxies beyond our own, and imagined deep space for the first time. He seems to have been one of the only persons of his time, followed by Erasmus Darwin, to begin to apprehend how vast the universe really is. Besides his astronomical observations, Hershel discovered the existence of infrared light, which opened up the spectrum beyond the visible light. The recent discoveries of Kepler-452b and TRAPPIST-1 – possible Earth 2.0’s – have revived the discussion of possible extraterrestrial life once more in the last years. Launched in 2015, the 100 million dollar project ‘Breakthrough Initiatives’, founded by Yuri Milner, a Silicon Valley-entrepreneur of Russian origin, is the largest initiative to seek scientific evidence of life in the universe. China is catching up in this domain with its development of its radio telescope FAST. Similar to the Low Frequency Array Radio Telescope (LOFAR) in The Netherlands managed by ASTRON, FAST will support the research of the Dark Ages that occurred 400 million to 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

KD The concept of deep time relates to the immense magnitude of non-human history that shaped the world as we perceive it today. Recently, discussions about the Anthropocene have entered the public sphere. We spoke about The Blue Marble image and its influence on our perception of space – perhaps our understanding of time throughout the ages has changed in the same way. Since Galileo Galilei’s invention of the pendulum clock, through Eadweard Muybridge’s motion study photographs, to today’s perception of time through social media ‘timelines’, it seems the concept of time is in perpetual change.

MD Indeed, the perception of time and space change drastically during the Industrial Revolution in particular. According to Rebecca Solnit, ‘Time ceased to be a phenomenon that linked humans to the cosmos and became one administered by technicians to link industrial activities to each other.’ The industrialisation and standardisation of time ran parallel with the discovery and influence of deep time. Lunar member James Hutton published his Theory of the Earth in 1788, which had a great impact on the thinking about the evolution of the features of the earth by means of natural processes over geologic time. Now considered one of the fathers of modern geology, Hutton developed his theory of the age of the earth after indexing different geological strata at places such as a cliff at Siccar Point in Scotland. Hutton recognised that layers of rock sediment were created by slow processes over such a long period of time that even the newest layers of the earth are made up, in his words, of ‘materials furnished from the ruins of former continents’. Just as during the industrial age ideas around deep time and the ecosystem were debated, it was during that period that the rapidly changing human activity on the planet began to actively impact it. On 28 April 1784, James Watt’s patent for a steam locomotive was granted. This date has initially been considered the beginning of the Anthropocene, a new geologic epoch defined by the massive impact of humankind on the planet, by Dutch chemist and Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen, when he coined the term in 2000. The existence of the Anthropocene and its possible beginning, currently considered to be parallel to the start of the atomic age, are still critically debated but the effects of global warming are being felt around the world. The thinking about the ecosystem and the importance of oxygen for life on our planet was present in the exchanges between Lunar member Joseph Priestley and Lunar guest Benjamin Franklin. Together they laid the foundations for the discovery of oxygen (which Priestley called ‘dephlogisticated air’) and photosynthesis. The experiments of Priestley revealed that plants produce oxygen and were instrumental in Franklin’s recognition that the production of breathable air is part of an interconnected system – a system that links animal and plant life with invisible gases, and that in turn the cutting down of trees or forests can have an impact on the ecosystem.

KD Apart from deep space and deep time, one of the LUNÄ talks engaged with the concept of ‘deep evolution’. How we understand the human capacity for wisdom, where it came from, and how it emerged are the basic questions of theoreticians who engage with the subject. The discussion tackled the notion of the post-human – a concept that has emerged from the fields of science fiction, philosophy and contemporary art. Post-human denotes a person or entity that exists in a state beyond being human, quite literally. Could you elaborate on the connection between these concepts?

MD ‘Post-human technologies’ have the potential to make deep space travel a possibility, no longer to be fantasised about. Projects like the 2045 Initiative, founded by Russian entrepreneur and billionaire Dmitry Itskov, aim to create technologies enabling the transfer of an individual’s personality to a more advanced non-biological carrier, and extending life, including to the point of immortality. Istkov plans to live 10 000 years. The search for longevity has a strong overlap with another science- fiction-like area that is fast approaching reality – artificial intelligence (AI). Many of the young billionaires interested in AI, often from Silicon Valley, made their fortunes handling chips and algorithms and big data as they created the information technology revolution. The thinking around artificial intelligence has roots in the 18 th and early 19 th century. Ada Lovelace, an English mathematician and writer, is mostly known for her work on the early mechanical general-purpose computer developed by Charles Babbage, a close friend of William Herschel. Her notes on the engine include what is recognised as the first algorithm intended to be carried out by a machine, and she is often regarded as the first computer programmer. In her notes from 1842, Lovelace dismisses artificial intelligence and writes that the ‘Analytical Engine, a mechanical computer, has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis, but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths.’ This argument is still relevant in the discourse around AI. A universe or multiverse inhabited by other civilisations has long been a source of inspiration for critical fiction writers who use these other worlds to imagine alternative societies. All science fiction is to some extent an exercise in the fantastic imagination, through the conceptualisation of alternate worlds, but they are also exercises of the political imagination. The fantasy that humans might simply start over on another planet is dangerous, according to sci-fi writer Kim Stanley Robinson, as it neglects responsibility for earth, our one and only home. We often have trouble imagining what a positive future looks like. If we want a better future, maybe we need better stories.

____