Essay

Jes Fernie for P.E.A.R. (Paper for Emerging Architectural Research), Issue No 6, Landscape/Ecology 2014

When the poet John Clare was admitted into an insane asylum in 1837, it was commonly understood that the cause could partly be put down to the effects of the Enclosures Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries. Introduced by Parliament in order to increase productivity but also to limit the number of commoners who had access to land, the Acts radically changed the psychological and as well as physical landscape of Britain.

Land that was previously accessible to commoners was closed off, leaving a drastically reduced set of options available for people to graze their animals, fish and hunt, cultivate the land and escape their squalid living conditions. Perhaps most damaging of all, the Acts resulted in psychological scarring on a huge scale, constraining the human spirit and shutting down access to other worlds.

Before the Acts came in to force, John Clare could often be found drinking and singing with local gypsies under a tree near his home in Helpston, East Anglia. Escaping the limited set of expectations set by his peers (mainly wealthy poets in London), his family and in all likelihood himself, the tree and its surroundings represented a space where he was free to express himself in any way he wished. He refers to this tree in his poems as the ‘Langley Bush’.

During the Anglo Saxon period, the site of this tree was an open-air court attended by representatives from surrounding parishes who met twice a year to judge serious crimes. The court was presided over by the Abbot of Peterborough who dictated the terms of use for the gibbet (a gallows-type structure). Clare, along with his neighbours, friends and work mates, was probably aware of this rich and murky background, which added another layer of historical weight to the site.

The tree became a victim of the Enclosures Acts and was removed. Soon after, the Vagrancy Act of 1824 made it an offence ‘to be in the open air, or under a tent, or in a cart or wagon, not having any visible means of subsistence, and not giving a good account of himself, or herself’. Clare and his gipsy comrades were disenfranchised to the core. In a diary entry made on 29 September 1824, Clare states that ‘last year Langley Bush was destroyed an old white-thorn that had stood for more than a century full of fame the Gipseys Shepherds & Herdmen all had their tales of its history and it will be long ere its memory is forgotten.’

One hundred and seventy years later, in 1996, the John Clare Society proposed that a tree be planted in the area to commemorate and celebrate Clare’s legacy. Farcically, the chosen site was on private land. To visit the site without permission, one must trespass on land acquired from the commons during the Enclosures. Today, the tree is a symbol of restrictions to freedom – from the 19th to 21st century – as well as a representation of misguided nostalgia for the past.

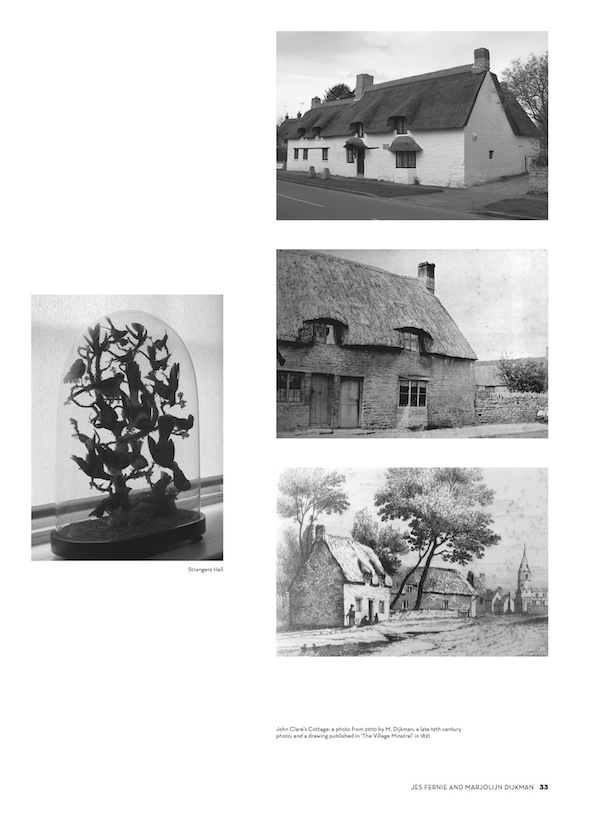

John Clare’s cottage in Helpston was bought by the John Clare Trust in 2005 and after a period of refurbishment, opened to the public in 2008. Like most museums of its kind, it struggles to strike a balance between the often opposing demands of authenticity and nostalgia. Rooms are replete with displays of ‘how they once lived’ but are devoid of any political or social context. Any acknowledgement that the museum is situated within a geographic area fraught with social and economic challenges, many of which hold parallels with John Clare’s life, is entirely invisible (the living conditions of Eastern European farm workers in and around Peterborough is an obvious example). As the British Marxist Historian Raphael Samuel has written ‘Heritage becomes the fulcrum that eases present discontinuities (labour protests, reports of sexual gender and racial discrimination, identity politics etc) into a position of timeless harmony.’

The rise of the multi-million pound heritage industry in Britain was brought about by Margaret Thatcher in the 1970s. While stoking the fires of capitalism she was also establishing English Heritage – an act that has been viewed by some as a response to the loss of Empire and the threat of assimilating English identity to the EEC. Thatcher very cleverly balanced her drive to create opportunities for enterprise, innovation and capital growth with an appeal to the continuity of tradition in heritage. While the rate of change stormed all around us, ‘pastness’ was inserted into the popular imaginary’ – a common inheritance that gave the British public a strong sense of identity.

Recent right wing political leaders and parties have taken a more direct route to harnessing nostalgia for the past in order to gain public support. The Tea Party’s adoption of historical costumes from the 18th century Boston Tea party is an obvious example, but Geert Wilders, leader of the Party for Freedom in The Netherlands, is the perhaps one of the most fantastical, with his adoption of the character of Michiel de Ruyter, the 17th century Dutch admiral. In his campaign film, Wilders travels through the Dutch landscape on a rowing boat, dressed in flamboyant admiral garb, delighting in the pastoral idyll of a past never realised, boldly enlisting the imagination to fight the status quo.

Our obsession with holding on to, and preserving an idealised view of the past is literally strangling our ability to create new futures. In a lecture at the Royal Academy (London) in 2011, architects from OMA presented a diagram showing that 12% of the world’s surface is now preserved, much of this through UNESCO’s World Heritage programme. Buildings and sites are being preserved at such a rapid rate that the time span between the creation of an object and its preservation is reducing to the point that preservation is in danger of becoming a prospective practice, ‘…heritage is becoming more and more the dominant metaphor for our lives today’.

How we tell the stories of our past, and the selection process that inevitably goes on when we tell them, are issues that all historians, museologists and UNECSO officials must all grapple with. John Clare spent forty years in that asylum, trying to come terms with the implications of his story.

_

Notes

1. Samuel, Raphael Theatres of Memory. London and New York: Verso 1994

2. An argument put by Ryan S Trimm in his essay Haunting Heritage and Cultural Politics: Signifying Britain Since the Rise of Thatcher, 2005.

3. See article by Merijn Oudenampsen, Political Populism: Speaking to the Imagination, Open 2010/No.20/The Populist Imagination