Conversation

The Art of Place

The Creativity of Place

Michael: How important is place in your art, and in creativity more generally?

Marjolijn: Place and its specific characteristics, organization, politics, etc., is very important in my work, and most of my works are made for a specific place in a specific moment in time. My work has developed over the last ten years from being quite site-specific, mainly working on and for a specific location, towards a practice that focuses on particular locations and interconnects issues or characteristics within a more global framework. In this way one place could become the starting point and inspiration for a work on site, but could also become more abstract, something that travels along with me, gets stuck in my memory and influences the experience of other places I visit. By taking pictures I can take bits of these places with me and connect them together within a bigger structure of an ongoing, growing archive.

Michael: Since you obviously take so much inspiration from the place you work, let me ask: Where do you prefer to work? What happens when you move to a different work environment?

Marjolijn: I use my studio to reflect on the situations I have encountered and filter the gathered information with which to start working. I love that quiet space. And I love to work in my own country, since I know the culture, the politics, and it is interesting for me to challenge these. But then again I love to travel and get to know new places, learn about other cultures, and gain a bigger understanding of what’s going on in the world.

Michael: And what has been your response to California, or more specifically, the Bay Area?

Marjolijn: One thing I noticed in particular while researching the area for my project is the amount of knowledge organizations in California—databases, archives, server farms like Flickr, Archive.org, Wikipedia, Google and many others. They all seem to be located around the Bay Area, and I wonder why. What’s your reaction to California?

Michael: I love it. Someone once told me California is the place to come if you want a second childhood! Peter Sellars said that California is the place where people come to try new things. New York and Chicago reminded him of what America was, but in California, the question is: what will America be? Of course, it’s never that simple. Amalia Mesa-Bains, a Chicana artist friend of mine, wrote: “I think it’s hard for people to understand that all the time California has been California, it’s always been Mexico. There is a Mexico within the memory, the practices, the politics, the economy, the spirituality of California. It’s invisible to everyone but Mexicans.”

Creativity is obviously a very personal thing, but there’s no doubt that creativity takes place. That is to say, creativity occurs in specific locations, but also that it requires space for its realization. Creativity in place refers to the role that a particular location, or time-space setting, has in facilitating the creative process: think for example of fin-de-siècle Vienna, Silicon Valley, or Hollywood. Creativity of place refers to the ways in which space itself is an artifact in the creative output, as when a dancer moves an arm through an arc, or a photographer crops an image to create a particular kind of representational space. The simplest creative acts are fraught with geographies that instruct the spectator how to see, that also hide things from us. To me, space is fundamental to the creative act, and I warm to the creative place that is California.

Marjolijn: So it’s all about the way we react to place and how we manipulate space?

Michael: That’s a nice way of putting it, but it’s even more than that. The city itself may become a crucible of artistic innovation whenever a critical mass of artists is assembled. Perhaps one of the most famous examples is fin-de-siècle Vienna. Place acts too as an inspiration for art. In a landmark study of visual arts and poetry in California from 1925 to 1975, Richard Cándida Smith accords great weight to the State’s relative isolation as a stimulus to creativity. It was not that California artists desired isolation, but that the tabula rasa represented by California offered the opportunity to strike out against the primacy of New York and Europe. The specifics of place become the subject of art. For instance, Alfred Steiglitz saw New York as a great machine which offered artists a unique opportunity to comprehend the modern. At another level, place influences the reception of an art object. In her memoir of Iran Azar Nafisi points out how Nabokov’s Lolita becomes a different book if it is read by a Muslim who does not regard the novel’s eponymous heroine as an underage girl. Finally, places can be transformed into broad agglomerations of dynamic artistic and social change brought about by the synergies of geographical ensembles of cultural producers, consumers and markets that congeal in a particular place and time. The processes of art-making, distribution, and consumption define what Sharon Zukin called the “artistic mode of production,” in which cultural production and consumption are combined through a set of market practices.

Marjolijn: Do you think these ideas about the role of place in artistic production are generally accepted?

Michael: Probably not. In 1974, in one of the earliest sustained assessments of West Coast art, Peter Plagens agreed that geography mattered in what artists created and what happened to their work. However, by 1999 he appeared to have changed his mind, writing that “geography is a much less significant factor in … West Coast art than it was a quarter-century ago.” That may be so, but I firmly reject the notion that time and place have lost their purchase in creative life: noone can be liberated from the constraints of space; very few artists would wish to be.

Marjolijn: I agree, but how has this anti-place spirit arisen?

Michael: Partly because space is not adequately theorized in studies of the creative process. Place is everywhere in film and photography, for example, from the choice of subject, through the placement of camera, to the composition of image. Yet according to David Clarke, by far the most popular way of studying film covers a theoretical terrain triangulated by semiotics, psychoanalysis, and historical materialism. Or to put it more simply: the image, how it is received, and the social context.

Marjolijn: It seems there’s no place for place in that!

Michael: Precisely. This is why I invented the term “photography’s geography” to encompass the entire set of place-based contingencies in photographic practice. These include: the place of production, which incorporates both the specific site of photography, but also the circumstances of the ambient artistic mode of production (particularly the market for photographic images); the production of place, including the narrative and compositional aspects of the image, as well as the spatial techniques employed by the image-maker (camera angle, depth of focus, etc.); the place of presentation, referring to the image and its mode of presentation (on a website, in an album, or on a gallery wall); and reception in place, what happens to an image when it is released to the world of consumption (including purchase).

The Belly Shot

Michael: Tell me more about how you approach the task of photography, especially your now-famous ‘belly shot’ that we’ve discussed before?

Marjolijn: I use photography in different ways. Within the presentation of site-specific projects, it has a quite documentary approach, representing actual situations on site that I encountered and that motivated me to develop the piece. Within that context, the images are totally connected to the place; the geographical location, politics, culture etc. On the other hand, the same images can become part of the big archive piece such as Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, where they are dislocated from any ordering.

Technically, I always use a camera with a small viewfinder on a screen. I never look through the viewfinder on the camera above the lens, but rather I am holding the camera at waist height to be able to view the situation and see the image on the camera simultaneously. This method creates a specific perspective in the images. Somebody once mentioned it was the perspective of a child because of the low height, which I thought was a nice idea.

The Human in the Map/ Psycho-geography

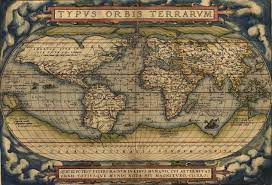

Michael: Let’s talk about maps for a while. How did you choose the title of your show at BAM?

Marjolijn: The Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, or Mirror/Theatre of the World, was the first printed modern Atlas as we know it. It was compiled by Abraham Ortelius and published in 1570. He collected the most accurate maps from all over Europe, and was the first to include five continents and a single index. Although he traveled in Europe and was in close contact with many cartographers, he never really ventured outside of Europe to encounter the world he was representing. In this period, Belgium and the Netherlands and other countries in Europe were establishing the foundations of what later became the market-driven globalized world. In the Netherlands, where the first stock market was developed, two months ago they discovered the oldest stock in the world, from 1602. Colonization went hand in hand with mapping “undiscovered” lands. In those days, mapping land was something similar to appropriating land. Maps create an abstraction of place and that abstraction has been very helpful for many people to navigate, but also to invade and to exploit. The idea of an overview of the world, seen from a god-like perspective, fascinates me but it scares me at the same time.

My atlas consists of many little details and gives a view from ground level. The situations I encounter, and photograph, act as agents, reflecting and performing in this Theatre of the World. By indentifying a human gesture in the landscape, the landscape reflects both how we organize our surroundings and how we organize each other. I consider the archive as a kind of collective self-portrait. I sometimes feel that we shape the landscape in a certain way, and that it shapes us in return by making us behave in a certain way. I’m interested in this circle.

Michael: It struck me that you almost seem to be taking a random walk through cities in search of something. I’m reminded of Guy Debord and the Situationists in 1960’s Paris, and what they called psycho-geography. They deliberately got lost in the city so they could discover it anew.

Marjolijn: I do sometimes feel like a nomad, like most people who travel a lot. The photographic archive is only one part of my practice, so in the hours I’m walking around, I feel like a flâneur wandering the city streets with no clear directions, which I actually like the best. But there is also a need to make projects more connected to a single place, site, or subject so as not to feel alienated from my surroundings. Photography is a great medium to capture the moment, to collect a situation without “touching” it, but ultimately there is still a machine between you and the world. So yes, I love to wander but I also feel an urge to touch ground, and find a position between all the things that are already there. I guess this is my motivation to make works on site.

Michael: The Situationist theory of the dérive (their conception of a purposeful drifting through space) seems to be enjoying something of a renaissance in my field, I think because it captures the difference between material and mental geographies, that is, between the material conditions of human existence, and an individual’s cognitive/perceptual response to those conditions. Think of it as the distinction between the city of fact and the city of feeling. I was surprised that there are no people in your images? It felt to me that you were anonymizing these places, perhaps even rejecting the link between the material and the mental?

Marjolijn: I’m interested in any kind of human expression that occurs when people are busy and nobody notices. For instance, instead of being in contact with and talking to people, sometimes you find out more about them by just moving through their home and seeing how they organize their space. The details you find, the way they order their lives, is quite telling about who they are.

Here Be Dragons / New Lands

Michael: In one of your video projects, Surviving New Lands, you make the link between people and place more specific. You portray the construction of a new port in Rotterdam by approaching the territory from the sea, taking the viewpoint of ocean explorers. As you come close to the unknown land, the viewer is bathed in stirring music from old movies and hears the spoken phrases from ancient explorers as they encountered the unknown. It’s a lovely work that recalls Lewis Carroll’s poem “The Hunting of the Snark,” in which a motley crew sets out on a hunting expedition, navigating with an “ocean-chart” that has no vestige of land on it, no functioning scale of distance, no lines of latitude and longitude. The crew members each possess a specialized skill that is perfectly useless to the task at hand.

Marjolijn: I love that map! I think it is a very nice way to playfully challenge the system. Sometimes certain practices become too accepted and institutionalized, and nobody seems to wonder how they became that way or if they still could be changed or turned the other way around. The big risk taken by anyone who creates an alternative system is that it will eventually be institutionalized itself as the new order of things. For me this is one of the biggest challenges, and I’m trying to find the right balance in this. Long-term projects are very interesting for many reasons, but they need to stay flexible and avoid becoming too institutionalized. A similar problem occurs in most other projects, both academic and artistic, don’t you think?

Lewis Caroll: The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony, in Eight Fits; with nine illustrations by Henry Holiday (London: Macmillan, 1876)

Lewis Caroll: The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony, in Eight Fits; with nine illustrations by Henry Holiday (London: Macmillan, 1876)

Michael: Yes, but to return to your earlier point, most exercises in exploration and mapping were designed to establish institutional control, as when Spain conquered the new lands eventually called the Americas. Colonialists and conquerors, with their mapmakers, were primarily interested in establishing new world orders with themselves in control.

Marjolijn: Even so, all such empires never lasted. Nothing is permanent about world politics!

Michael: True. The U.S.-Mexico border is currently a war zone, at least that’s the message being conveyed by politicians and media on both sides of the international boundary. In the U.S. the national debate on immigration reform fixates on the estimated 11 million undocumented people in the U.S. Successive federal governments promise that sealing the southern border will stop the influx of Mexicans (and terrorists), while others point out that attention is better directed toward the 40 percent of the undocumented who have entered the U.S. on legal visas and simply overstayed. In Mexico, national headlines are dominated by the government’s war on the drug cartels and the thousands of deaths it has caused, but border media also give full attention to the decline in cross-border tourism, which is murdering local economies.

My experience of the U.S.-Mexico border zone is different. For over a decade, I‘ve explored the entire length of the border on both sides, a total of 4,000 miles plus a thousand more for detours and revisits. I had the good/bad fortune to begin my explorations before the U.S. government announced plans to build walls between the two countries. Digging into the past, I found no precedent for such a partitioning in the two nations’ histories. Instead, I encountered on the ground many well-connected cross-border communities getting on with life without interference from the respective national capitals, in a kind of territorial coexistence that I call a “third nation.” I’m spending a lot of time now trying to map that new territory

Marjolijn: Do the walls being built between Mexico and the U.S. work?

Michael: No. They are already being breached by trucks fitted with ramps that allow vehicles to drive up and over the walls; the high fences of unclimbable mesh are simply removed to permit passage and afterwards carefully slotted back into place; a network of underground tunnels allows illicit border-crossers to bypass the surface fortifications altogether; and border crossings have become an organized industry. Fortress USA is using a blunt geopolitical instrument—partition by walls and fence—instead of constructing connective tissue. The term “third nation” refers to a super-national shared identity among the border communities, where people recognize and cherish the interdependencies upon which their collective future depends. We should cultivate the third nation along the US-Mexico borderlands. It is already demonstrating a different way for our two nations to relate.

Mexico – US border, photo by Michael Dear

Words, Gestures, Objects

Michael: Despite the emphasis on the visual in your work, I notice that your supplement your images with a list of words, verbs to be exact. Where does this taxonomic urge come from? It’s almost as if the artistic side of your brain is constantly arguing with a more forensic, almost scientific tendency in another part of your brain.

Marjolijn: You’re right. In a way, it is a forensic tendency but one that also plays around with the meaning of a word in relation to an image (or the object/situation represented by it). I use the words to challenge systems of perception and identification. For me, the moment of taking pictures and the ordering of the pictures is not completely separate. The moment you add a word to an image many new things happen, and a whole new game begins.

Michael: As a geographer confronting your panorama, I couldn’t help but feel some irritation that you deliberately elected not to tell the viewer the precise location of the photographs. Why did you omit this information?

Marjolijn: In contrast to my site-specific works, in the archive I deliberately omit mention of the locations where images are made. This creates disorientation because the images are all mixed up together. I like to present a different form of orientation, one directed by a gesture that most often seems quite universal. Although different in shape, in production, and created with different material and/or financial means, many of the things I encounter seem to relate to other things around the world. If I would add the location of an image, so many other connections would influence the way you looked at it. In this case, I prefer to not provide that information!

Michael: And yet you give clues about the photo locations elsewhere in the archive?

Marjolijn: Well, sometimes you will see some text somewhere, or recognize a particular type of landscape which makes it possible to situate the image. Then again, a lot of times people may be familiar with the locations where I took a picture but don’t recognize the things I recorded…

In the panorama, I don’t mention the words/gestures. I’m interested in the Myriorama, a set of illustrated cards that 19th-century children could arrange and re-arrange, forming different pictures in any order where the horizon was matched. The word “myriorama” was invented to refer to myriad pictures, following the model of the panorama. In my panorama the images are not arranged according to a line in the landscape, but perhaps in a more associative way. Every time I assemble a new panorama, the images are re-used in new combinations.

By the way, even though you are deeply engaged in art, I notice that you use words a lot!

Michael: Sorry, I’m a professor not an artist. Words are used to categorize, to open up levels of abstraction and understanding. For instance, space, you might say, is nature’s way of preventing things from happening in the same place, on top of one another. Much of French philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s work is a fugue on this proposition. In the course of his famous 1971 work, The Production of Space, Lefebvre identifies the following kinds of space: absolute, abstract, appropriated, capitalist, concrete, contradictory, cultural, differentiated, dominated, dramatized, epistemological, familial, instrumental, leisure, lived, masculine, mental, natural, neutral, organic, original, physical, plural, political, pure, real, repressive, sensory, social, socialist, socialized, state, transparent, true, and women’s space. At the end of all this, there can be little doubt that, as Lefebvre writes: “space is never empty: it always embodies a meaning.”

Marjolijn: It’s odd the way “women’s space” is tacked on at the end!

Michael: Yes, well, the list is alphabetical! But remember, Lefebvre was writing 40 years ago. He would certainly have added other categories if he was writing now.

Marjolijn: Such as?

Michael: Such as: border, hybrid, virtual; maybe identity, citizenship; certainly liminal.

Marjolijn: How do you get words to work for you?

Michael: Through writing, naturally, but often in conjunction with maps, photographs, or art works. I like to put these different media in conversation with each other, which is also what you do, I think. Similar to you, I’m trying to construct cartographies of the city from collages of words and images, signs and icons that together capture the way cities are being made. Look at my map of the city, and perhaps you’ll see what I mean. Sometimes I’ll start with a visual prompt, other times with words. For example, if I want to describe the major social forces currently affecting our lives, I could start with what you describe as your archive’s ”collective self-portrait.” Or, I could begin with words, such as: globalization, meaning the emergence of a relatively few world cities as centers of command and control in a globalizing world economy; network society, or the rise of the “cyber-societies” of the Information Age; social polarization, referring to the increasing gap between rich and poor; hybridization, the reconstruction of identity, citizenship, and culture brought about by international and domestic migrations; and sustainability, including a widening consciousness of the need to contain human-induced environmental change.

Marjolijn: Are you saying that my visual archive and your verbal categories are equivalent ways of understanding the world?

Michael: Exactly so. Equivalent but different. I use theory to inform my thinking about art and society; and I use art as a stimulus to new theoretical insight. But I need both vocabularies to better understand the world. Here’s an example of what I mean. Early landscape photography in America often portrayed featureless roads, emphasizing distance, remoteness, and desolation. But then artists such as Garry Winogrand, exploiting the early 1960’s car culture and mobility, took photographs from a moving vehicle. The car’s hood, streaked windshield, dashboard, and interior roof imposes a frame within a frame. The windshield became a screen upon which the swiftly-passing images of daily life were projected. And this, of course, is a critical historical juncture. Mobility, speed, and the screen utterly transformed late twentieth-century visualization and cognition. In Jean Baudrillard’s phrase: “The vehicle now becomes a capsule, its dashboard the brain, the surrounding landscape unfolding like a televised screen.” In today’s digital world, the screen is king.

In this fluid spatial and temporal milieu, geography and art should work together in understanding and representing the world. In different ways, artists do what geographers do— they offer ways of observing, describing, studying, ordering, and classifying the world. One way or another, both of us engage in the cognitive process of knowing past, present, and future worlds.

2019

Marjolijn: For a biennal in the United Arab Emirates, I was inspired by huge real-estate billboards that were forecasting beautiful science fiction-like futures. So I decided to research the way the future was being visualized in science fiction films. I figured out the dates in which each film was set, such as Blade Runner in 2019, Johnny Mnemonic in 2021, Children of Men in 2027 and so on. Then I prepared a video collage of the future representations organized along the dates which the movies purported to represent. This film was called Wandering through the Future, and consists of fragments from 70 international film productions, representing all sorts of apocalyptic landscapes and scenarios. The one-hour video leads you through a future from 2008 until 802.701 A.D. It examines the way the future has been given shape and how the different scenarios relate to one another. I thought all these worst-case scenarios including natural disasters, utopian and dystopian cities, viruses, clones and other planets might provide insights into our fears. I didn’t find many positive films about the future. The most recent productions are certainly the most fearful. Films made in the 1960s and 1970s showed a more optimistic future.

Still of ‘Wandering through the Future’, Marjolijn Dijkman, 2007

Michael: That’s intriguing, because I’ve studied movies about the Mexican-U.S. border from the past half-century, and they’ve shown a marked drift toward the deeply pessimistic, too. For example, Border Incident (Anthony Mann, 1949) is an optimistic story of U.S.-Mexico cooperation to aid undocumented border-crossers and eliminate corruption on both sides. But nowadays, when the drug cartel’s reach had gone global, a movie like No Country for Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007) is frighteningly violent and nihilistic throughout its entire length. As to the future, in Sleep Dealer (Alex Rivera, 2008) the border is completely sealed and entry to Mexico is prohibited except to credentialed personnel. In a world of cyber-connections, Mexican workers in Tijuana plug into robots on the U.S. side that remotely execute their work in construction, cleaning, etc. As one character cynically remarks, this vision of the American Dream provides the U.S. with “all the work…without the [Mexican] workers.”

Marjolijn: This makes me think about the way European cartographers used to visualise the unknown. Because they’d never seen a place, they often drew monsters and dragons on the map in the location where the country would be. They simply emphasized just how subjective their representations of place were. For instance, in China dragons were associated with water in ways that hinted at profit and prosperity! I think that something we have in common is the search for ways to investigate representations and perceptions of a place in order to challenge them and contribute to changing them.

Michael: That’s true. Ever since I was a schoolboy, I’ve loved maps. But I soon learned you couldn’t trust them.

Marjolijn: Why do you say that?

Michael: When I was in elementary school in Wales, our world atlases always had Britain and its empire in the front of the atlas, and the rest of the world at the back. All British “possessions” were colored in red—Canada, Australia, and so on. It looked to me as though we owned the world! Only later did I realize that the atlas didn’t really represent the world as it was; it was only a memory or trace of some long-dead British imperialist ideal. I admit that, as a child, I thought our “red world” was pretty cool. Then one day I found a different atlas that showed the countries of the world on the same scale; you could fit the entire British Isles into the U.S. state of Texas, and still have room left over for the Netherlands and Belgium!

____