Essay

Jonathan Watkins

LUNÄ installed at Spike Island, Bristol, UK (2011)

LUNÄ installed at Spike Island, Bristol, UK (2011)

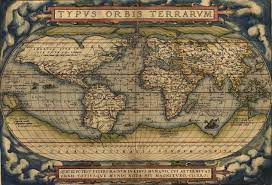

Much of Marjolijn Dijkman’s work is concerned with the business of collecting and classifying information. It problematises our reliance on institutionalised systems in order to assert the politics of assumed knowledge. Two works, in particular, are explicit in this respect. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is an ongoing project, a vast pictorial archive devised by Dijkman as a kind of 21st- century equivalent of Abraham Ortelius’s Theatre of the World (1570), often cited as the first atlas. She maps our planet by accumulating digital photos she herself has taken while travelling. A selection of these, produced in varying sizes, have been pasted onto gallery walls in venues across the world including Ikon and Spike Island (UK), Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo (Mexico), Berkeley Art Museum (US), MuHKA (Belgium) and FRAC Nord Pas de Calais (France). By depicting human intervention in nature, the artist makes an anthropological survey, pointing out similarities and fallacies in our efforts to improve the world – by making it more efficient, comfortable and beautiful – whilst communicating a whimsical sense of humour in the process.

LUNÄ (2011) is a complementary project by Dijkman which includes a replica of the Lunar Table. The original piece of furniture is now on permanent museum display at the Birmingham address where members of the Lunar Society, including Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley, James Watt and Josiah Wedgwood, would meet each month near the full moon to further the causes of the 18th-century Enlightenment. They spent hours sitting around it, dining, swapping notes that were to have a pro- found influence on our society, propelled by an aspiration to relentless growth, courtesy of capitalism. This is not to say that the Lunar Men were the root of all modern evil. More often than not it is a bastardisation of their thinking that has prevailed, and their testing scepticism (vital for scientific research) is something too easily ignored or for- gotten. It is tantalising to imagine how they might get on now, 200 years later, putting their heads together to reflect on havoc wreaked by the Industrial Revolution, its concomitant imperialism and rampant urbanisation, its geopolitical and environmental disasters, in a conversation conjuring up new theories in pursuit of sustainability and fairness for everyone.

Dijkman’s title for her work, LUNÄ, is faux-Scandinavian and thus not only refers to Boulton et al, but also to the make-the-world-a-better-place branding of Ikea. This was reiterated by the actual Ikea chairs that she placed around the table, serving to emphasise the complex significance of her replication of the original table. The chairs were mere tokens of DIY and identical to countless others. The table, on the other hand, is the one and only copy of a very fine piece of furniture as well as a symbol of the zeitgeist that engendered such mass-production. Above everything, and unlike a chair, it strongly signifies possibilities of interaction, dialogue, conviviality and negotiation. People communicate across tables. At Ikon, its first location, LUNÄ was a place for appointments, impromptu get- togethers for visitors, college tutorials and club meetings as well as the focal point for a public programme of lively evening talks on aspects of education, medicine and science, urban design and regeneration, and the relevance – or other- wise – of art. Today, the table is at the centre of Dijkman’s initiative Enough Room for Space, in Brussels, attracting a wide range of artists, curators and academics, driven by the same lunar impulse to raise hard questions and consider radically different ideas as to what the future might hold. In this way LUNÄ still orbits in a blue sky.

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum and LUNÄ installed together at Spike Island, Bristol, UK (2011)

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum and LUNÄ installed together at Spike Island, Bristol, UK (2011)